Sunday, November 20, 2005

Crisis in Baku!

What election? We're talking about a real crisis here.

The supply of pirated DVDs has been drastically reduced in the last few weeks!

One of the biggest benefits to living in Baku was the endless supply of first-run movies -- summer blockbusters and independent films alike. Within days of almost any movie opening in the States, it could be purchased here for $5.

The pipeline seems to have been cut! First, our favorite DVD store closed -- the one with a better selection of classics and independent films than the average Hollywood Video. Then, the cheap Chinese purse store started selling mostly TV series (not that there's anything wrong with that. Lost is pretty good). But we can't hardly buy any new releases anymore!

The rumor is that Russia --the source of all Baku's fake DVDs -- cracked down on pirating. Aren't there bigger problems on which Russia should be focusing right now? Don't they know it's academy award season?

The supply of pirated DVDs has been drastically reduced in the last few weeks!

One of the biggest benefits to living in Baku was the endless supply of first-run movies -- summer blockbusters and independent films alike. Within days of almost any movie opening in the States, it could be purchased here for $5.

The pipeline seems to have been cut! First, our favorite DVD store closed -- the one with a better selection of classics and independent films than the average Hollywood Video. Then, the cheap Chinese purse store started selling mostly TV series (not that there's anything wrong with that. Lost is pretty good). But we can't hardly buy any new releases anymore!

The rumor is that Russia --the source of all Baku's fake DVDs -- cracked down on pirating. Aren't there bigger problems on which Russia should be focusing right now? Don't they know it's academy award season?

Thanksgiving Advance Work

Thursday was the National Day of Revival, thus a holiday, so M and I headed down to the Teze Bazaar to scope out the Thanksgiving products on offer. Teze Bazaar is sort of like our Costco -- if it's not there, in vast quantities, you probably don't really need it.

Is there anything that cannot be improved by pickling?

The Teze Bazaar is also the place to go for all kinds of meat products. Tripe, boiled sheep heads, trotters, tongue, even the forbidden meat-- it's all there. You have to a be little bit careful though. The floor is slippery with mystery slime and you have to duck shrapnel from "butchers" hacking away at carcasses with hatchets.

One-stop shopping at Teze Bazaar

I found the Turkey lady who supplied excellent birds last year. She was wearing the same green headscarf and had a varied selection of turkeys and chickens, already butchered and cleaned. A "free-range" tom in Azerbaijan isn't going to weigh more than eight pounds, and we have 20+ people coming for dinner, so I ordered two of her biggest for pick-up on Wednesday. Although she's not a particularly squeamish veg, M recused herself from the negotiation.

After exploring the old copper market and negotiating for Goychay pomegranates and mandarins from Lankaran, we decided it was time to head off to the wholesale liquor market (at least as important for Thanksgiving dinner as the turkey).

As we pulled out the bazaar, I saw one of those things that reminded me, as if it was necessary, that for all its nouveau riche vulgarity, Baku still has at least one foot planted firmly in the third world.

"Don't look, Don't look!" I yelled at M, who was paying off the guy who blocks traffic for you as you back out of the parking spot. I grabbed for my camera, since I am incapable of NOT looking.

A guy had opened the back of his Lada station wagon and pulled out by the horns the recently-removed head of a huge, hairy water buffalo.

She had just missed it.

Fortunately for her, the guy set the water buffalo head down on the sidewalk and returned to the station wagon. He pulled out the head of a much smaller black and white cow, grabbing, it like a bowling ball, thumb in the eye socket.

We screamed like little girls.

Gourds are nice, too

Is there anything that cannot be improved by pickling?

The Teze Bazaar is also the place to go for all kinds of meat products. Tripe, boiled sheep heads, trotters, tongue, even the forbidden meat-- it's all there. You have to a be little bit careful though. The floor is slippery with mystery slime and you have to duck shrapnel from "butchers" hacking away at carcasses with hatchets.

One-stop shopping at Teze Bazaar

I found the Turkey lady who supplied excellent birds last year. She was wearing the same green headscarf and had a varied selection of turkeys and chickens, already butchered and cleaned. A "free-range" tom in Azerbaijan isn't going to weigh more than eight pounds, and we have 20+ people coming for dinner, so I ordered two of her biggest for pick-up on Wednesday. Although she's not a particularly squeamish veg, M recused herself from the negotiation.

After exploring the old copper market and negotiating for Goychay pomegranates and mandarins from Lankaran, we decided it was time to head off to the wholesale liquor market (at least as important for Thanksgiving dinner as the turkey).

As we pulled out the bazaar, I saw one of those things that reminded me, as if it was necessary, that for all its nouveau riche vulgarity, Baku still has at least one foot planted firmly in the third world.

"Don't look, Don't look!" I yelled at M, who was paying off the guy who blocks traffic for you as you back out of the parking spot. I grabbed for my camera, since I am incapable of NOT looking.

A guy had opened the back of his Lada station wagon and pulled out by the horns the recently-removed head of a huge, hairy water buffalo.

She had just missed it.

Fortunately for her, the guy set the water buffalo head down on the sidewalk and returned to the station wagon. He pulled out the head of a much smaller black and white cow, grabbing, it like a bowling ball, thumb in the eye socket.

We screamed like little girls.

Gourds are nice, too

Wednesday, November 16, 2005

Someone Has Finally Said It

Dentistry in Baku

From the department of "funny stories that I'm glad didn't happen to me," read this about a visiting election observer who needed emergency dental care in Baku on a Friday night. Thanks to Registan for the link!

He probably doesn't want to know this, but there is a western-trained Turkish dentist in town with more modern equipment than most US dentists. I sure wouldn't go to him, but I know people who have and come out just fine, and anyway, this dental victim's standards didn't seem to be all that high.

He probably doesn't want to know this, but there is a western-trained Turkish dentist in town with more modern equipment than most US dentists. I sure wouldn't go to him, but I know people who have and come out just fine, and anyway, this dental victim's standards didn't seem to be all that high.

Monday, November 14, 2005

Badass in Dogistan

Caucasian Shepherds are complete badasses. This one stood about three feet tall. Usually two or three of them guard a flock and you don't just run up and say hi. They are absolutely vicious. No wonder: right after they are born, their ears, and sometimes their tails, are broken (I assume to give predators less to latch on to) and they are put in a dark box so their eyes develop. I'm sure that's what gives them their charming dispositions.

Indeed, that is a collar of nails around his neck -- defense against wolves or other predators who think they are bigger badasses than he is.

Indeed, that is blood on his paws and head. Not clear whether it's his blood, the blood of his victims or lunch leftovers.

Thanks to the Beckster, who took these out near Shamaxi.

Indeed, that is a collar of nails around his neck -- defense against wolves or other predators who think they are bigger badasses than he is.

Indeed, that is blood on his paws and head. Not clear whether it's his blood, the blood of his victims or lunch leftovers.

Thanks to the Beckster, who took these out near Shamaxi.

Saturday, November 12, 2005

Baku Fashion

A new photo series on Carpetblog! Remember, irony is not yet a language Azeris are comfortable speaking.

Post-Sovietka fashion still reigns in Baku

It was probably 60 degrees on this late September day

I am constantly surprised at how often I see grown men dressed identically in the streets of Baku

So this is in Nardaran, one of Azerbaijan's most religious and conservative villages, about 30 kms from Baku. These women are voting

This is a group of women in Nardaran checking for their names of the voter list

Post-Sovietka fashion still reigns in Baku

It was probably 60 degrees on this late September day

I am constantly surprised at how often I see grown men dressed identically in the streets of Baku

So this is in Nardaran, one of Azerbaijan's most religious and conservative villages, about 30 kms from Baku. These women are voting

This is a group of women in Nardaran checking for their names of the voter list

Elevator Etiquette

Sure, there's a lot going on in Azerbaijan but Carpetblog is a space for commentary on important topics, like elevator etiquette, not politics. Carpetblogger has no opinions on such issues.

Western organizations love to do trainings in places like Azerbaijan. If it were up to me, I'd give out grants for trainings on the proper use of and behavior in elevators.

Modern elevators are a relatively new arrival in Baku. Elevators in most Soviet-era apartment buildings are smelly, non-functional death traps the size of a coffin. The doors on elevators in government buildings slam shut like metal jaws and leave serious bruises in you're caught in between. It's better just to take the stairs. I'd be surprised if there's a functioning elevator outside of the Absheron peninsula.

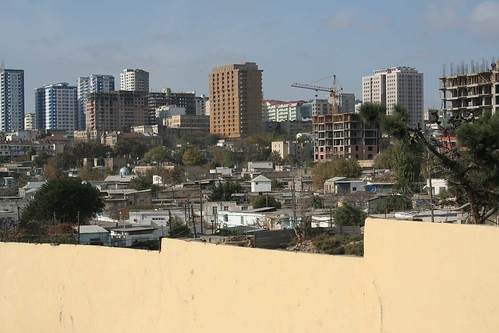

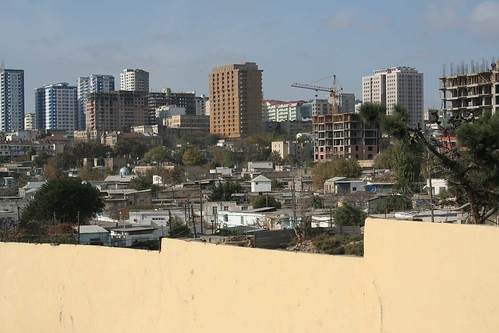

With this many highrises being built, elevator etiquette is more important than ever!

This means that many locals -- especially those from the regions -- are not up to speed with the way elevators are designed to work.

I work on the 13th floor of a brand new, modern office building, so this is a salient issue for me. It has several hundred people working in it. It has only three tiny elevators that hold no more than six people at a time. It can take 20 minutes to get downstairs at 6 pm when the building clears out.

Setting aside the design flaws of a 17-floor building that has only three elevators (yet rents per square meter on par with major European cities), things would go much smoother at rush hour if people used the elevator correctly.

My colleagues and I have noticed that some locals summon the elevator based on where it is relative to where they are, not the direction they want to go.

For example, someone standing on the 13th floor wants to go down, but the elevator is on the 8th floor. He or she pushes the UP arrow to call the elevator up, rather than the DOWN arrow to indicate he or she wants to go down.

This causes the elevators to make unnecessary stops, since inevitably, other down-goers who know how elevators work, push the down arrow. Correcting this would save countless minutes of my time -- time that would be much better spent sitting in the traffic that's bottled up in front of an 17 floor office building with no parking. (Urban planning would be another potential area where the west could share some "lessons learned" and "best practices.")

Needless to say, summertime hygiene, smoking policies and appropriate cell phone use would have to be included in the training.

However, since this training has to be culturally appropriate and take into consideration "local mentality" (my favorite common phrase in Azerbaijan), the custom that allows women to get on first, even if there are 10 men waiting for the six person elevator ahead of her, must be respected.

Western organizations love to do trainings in places like Azerbaijan. If it were up to me, I'd give out grants for trainings on the proper use of and behavior in elevators.

Modern elevators are a relatively new arrival in Baku. Elevators in most Soviet-era apartment buildings are smelly, non-functional death traps the size of a coffin. The doors on elevators in government buildings slam shut like metal jaws and leave serious bruises in you're caught in between. It's better just to take the stairs. I'd be surprised if there's a functioning elevator outside of the Absheron peninsula.

With this many highrises being built, elevator etiquette is more important than ever!

This means that many locals -- especially those from the regions -- are not up to speed with the way elevators are designed to work.

I work on the 13th floor of a brand new, modern office building, so this is a salient issue for me. It has several hundred people working in it. It has only three tiny elevators that hold no more than six people at a time. It can take 20 minutes to get downstairs at 6 pm when the building clears out.

Setting aside the design flaws of a 17-floor building that has only three elevators (yet rents per square meter on par with major European cities), things would go much smoother at rush hour if people used the elevator correctly.

My colleagues and I have noticed that some locals summon the elevator based on where it is relative to where they are, not the direction they want to go.

For example, someone standing on the 13th floor wants to go down, but the elevator is on the 8th floor. He or she pushes the UP arrow to call the elevator up, rather than the DOWN arrow to indicate he or she wants to go down.

This causes the elevators to make unnecessary stops, since inevitably, other down-goers who know how elevators work, push the down arrow. Correcting this would save countless minutes of my time -- time that would be much better spent sitting in the traffic that's bottled up in front of an 17 floor office building with no parking. (Urban planning would be another potential area where the west could share some "lessons learned" and "best practices.")

Needless to say, summertime hygiene, smoking policies and appropriate cell phone use would have to be included in the training.

However, since this training has to be culturally appropriate and take into consideration "local mentality" (my favorite common phrase in Azerbaijan), the custom that allows women to get on first, even if there are 10 men waiting for the six person elevator ahead of her, must be respected.

Drama in Dogistan, Part II

This story is a lot funnier now than it was when it happened.

A few weeks ago, we noticed that Mo, the most precious dogchild, had a small lump on his neck, opposite his now nearly-healed wounds. I figured it was a reaction to the injections he's been getting and chose not to worry about it. A few days later, the lump was the size of a lemon and Mo was very uncomfortable and lethargic.

Dr. Anar, the vet who makes housecalls, was called.

Readers of earlier editions will remember that Dr. Anar was elevated to vet of choice after the first vet was exposed as a quack.

Dr. Anar manipulated the lumps and found some others, but that was pretty much the extent of his examination. He looked up at me and declared his diagnosis with seriousness Marcus Welby would envy:

Cancer.

Keep in mind, I knew nothing about this person's education and background other than he'd neutered someone's cats with success; we didn't share a language; and I knew that the approach to and implementation of human health care in this culture is, politely, medieval. I also know that I know a lot about animal health.

Nevertheless, I believed him.

Hysterical plans were made to evaluate vet care options in Europe, since flying all the way home would be too traumatic for a dog with advanced cancer. Can dogs get chemotherapy?

After a couple of shots of Jack on the balcony, rational thought kicked in. Who can we call about this? Why not check with Terry, the Embassy doctor?

The very act of speaking to a person trained in modern health care and diagnostics talked us off a very narrow, slippery ledge. In a measured tone, Terry outlined all the reasons why the diagnosis was absurd, a conclusion rational people would have arrived at much sooner than we did.

I decided that almost 20 years of work around horses qualified me to diagnose and medicate as well as any vet here. I gave Mo some antibiotics and we went to bed.

The next morning, the dogs' most favorite people arrived -- Samaya the cleaning lady and Lena the Russian Dogwalker -- and much leaping about, running and barking ensued.

Suddenly, Mo's shoulder and neck burst like a balloon. I don't think I've ever been so glad to see several cups of pus on my floor and all over the walls.

Lena was rather surprised and after a quick examination announced what should have been obvious to any vet and probably me as well: He had three abcesses from the subcutaneous shots. Within minutes of them bursting, he was completely normal, if rather pussy.

Lena lectured me for not listening to her from the beginning, pointing out, correctly, that if I hadn't involved all these vets and followed her treatment that none of this would have happened. She scoffed at Dr. Anar's cancer diagnois and said Mo would live to be 100. I contritely agreed and assured her that I would submit to her authority on all dog-related matters from here on out.

For the second time in as many weeks, I stared into the abyss of "what do we do if something really goes wrong?" It's at this moment when living in a place like this ceases to be an adventure. I immediately regretted giving up the things taken for granted at home: high standards of medical knowledge and effective treatments; a common language; and common values, such as the value of an animal's life.

Mo's fine now, though. 100% normal.

A few weeks ago, we noticed that Mo, the most precious dogchild, had a small lump on his neck, opposite his now nearly-healed wounds. I figured it was a reaction to the injections he's been getting and chose not to worry about it. A few days later, the lump was the size of a lemon and Mo was very uncomfortable and lethargic.

Dr. Anar, the vet who makes housecalls, was called.

Readers of earlier editions will remember that Dr. Anar was elevated to vet of choice after the first vet was exposed as a quack.

Dr. Anar manipulated the lumps and found some others, but that was pretty much the extent of his examination. He looked up at me and declared his diagnosis with seriousness Marcus Welby would envy:

Cancer.

Keep in mind, I knew nothing about this person's education and background other than he'd neutered someone's cats with success; we didn't share a language; and I knew that the approach to and implementation of human health care in this culture is, politely, medieval. I also know that I know a lot about animal health.

Nevertheless, I believed him.

Hysterical plans were made to evaluate vet care options in Europe, since flying all the way home would be too traumatic for a dog with advanced cancer. Can dogs get chemotherapy?

After a couple of shots of Jack on the balcony, rational thought kicked in. Who can we call about this? Why not check with Terry, the Embassy doctor?

The very act of speaking to a person trained in modern health care and diagnostics talked us off a very narrow, slippery ledge. In a measured tone, Terry outlined all the reasons why the diagnosis was absurd, a conclusion rational people would have arrived at much sooner than we did.

I decided that almost 20 years of work around horses qualified me to diagnose and medicate as well as any vet here. I gave Mo some antibiotics and we went to bed.

The next morning, the dogs' most favorite people arrived -- Samaya the cleaning lady and Lena the Russian Dogwalker -- and much leaping about, running and barking ensued.

Suddenly, Mo's shoulder and neck burst like a balloon. I don't think I've ever been so glad to see several cups of pus on my floor and all over the walls.

Lena was rather surprised and after a quick examination announced what should have been obvious to any vet and probably me as well: He had three abcesses from the subcutaneous shots. Within minutes of them bursting, he was completely normal, if rather pussy.

Lena lectured me for not listening to her from the beginning, pointing out, correctly, that if I hadn't involved all these vets and followed her treatment that none of this would have happened. She scoffed at Dr. Anar's cancer diagnois and said Mo would live to be 100. I contritely agreed and assured her that I would submit to her authority on all dog-related matters from here on out.

For the second time in as many weeks, I stared into the abyss of "what do we do if something really goes wrong?" It's at this moment when living in a place like this ceases to be an adventure. I immediately regretted giving up the things taken for granted at home: high standards of medical knowledge and effective treatments; a common language; and common values, such as the value of an animal's life.

Mo's fine now, though. 100% normal.

Saturday, November 05, 2005

First Step: Admitting You Have a Problem

And the first step is always the hardest. The only problem I have is deciding which one of my latest purchases I like best.

This one is a 1946 Karabagh, with so many words woven into it that its weaver must have had a lot to say. Unfortunately, since they are all backwards, she must have been awfully distracted as well.

With five or six different kinds of animals represented it, it also tells a great story. The challenge will be trying to interpret it!

1946 is woven into the carpet

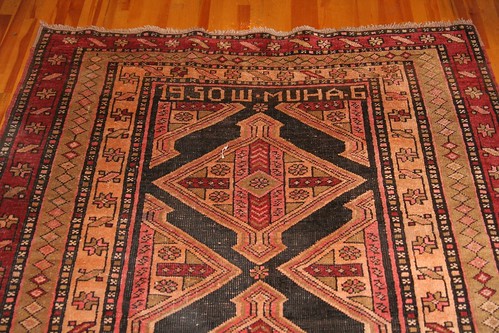

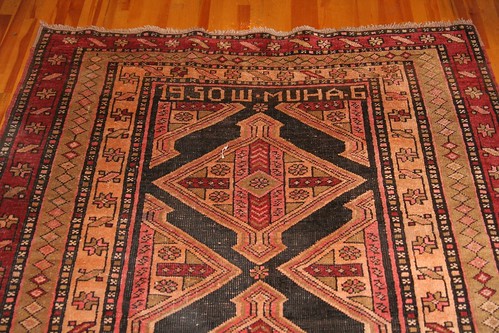

I bought this one at the same time. It, too, is Talish/Karabagh. It looks like a woman named Mina made it in 1950.

The cool thing about this one, besides its pattern, is that it's about 15 feet long!

Today, I had no intention of buying a carpet -- I only went into Ruslan's shop to pick one up I bought last week. The Producer and I were shooting the shit with Ruslan and his partner Ramiz. "Wait, Christina! My friend, he has antique in his car. I have never seen it. Do you want to look?"

That may have been a dumb question, but Ruslan is a very clever carpet dealer.

I have never seen a pattern nor color like this. It is an Avar carpet, made in the far northwest of the country, near the border with Georgian and Dagestan. It has a wonderful abrash (different shades of the same color that mark a different batch of colored wool.). It also has some knots in it that I have never seen before as well. I am going to have to do some research. It's not clear how old it is -- maybe 50 -75 years old.

This one is a 1946 Karabagh, with so many words woven into it that its weaver must have had a lot to say. Unfortunately, since they are all backwards, she must have been awfully distracted as well.

With five or six different kinds of animals represented it, it also tells a great story. The challenge will be trying to interpret it!

1946 is woven into the carpet

I bought this one at the same time. It, too, is Talish/Karabagh. It looks like a woman named Mina made it in 1950.

The cool thing about this one, besides its pattern, is that it's about 15 feet long!

Today, I had no intention of buying a carpet -- I only went into Ruslan's shop to pick one up I bought last week. The Producer and I were shooting the shit with Ruslan and his partner Ramiz. "Wait, Christina! My friend, he has antique in his car. I have never seen it. Do you want to look?"

That may have been a dumb question, but Ruslan is a very clever carpet dealer.

I have never seen a pattern nor color like this. It is an Avar carpet, made in the far northwest of the country, near the border with Georgian and Dagestan. It has a wonderful abrash (different shades of the same color that mark a different batch of colored wool.). It also has some knots in it that I have never seen before as well. I am going to have to do some research. It's not clear how old it is -- maybe 50 -75 years old.

Friday, November 04, 2005

Review: Pork Chop Shop

Since Baku lacks a bit in the service journalism department and so many foreign visitors are in town to watch the ruckus, I've decided to post some restaurant reviews I wrote a while back for a local rag.

Pork Chop Shop

Nothing about Xayal Kafe’s dowdy exterior hints at the forbidden fruit served inside. But this little hole in the wall – known among expats as The Pork Chop Shop -- is Muslim Baku's swine speakeasy.

The Pork Chop Shop (PCS) sits on a chaotic street near the train station, tucked among cell phone vendors and currency exchanges. It's furnished modestly, with molded plastic seats. Azeri men sit huddled at small tables, sipping tea and looking askance at women who step in through the front door.

The claustrophobic upstairs “loft,” reached by passing through the kitchen (shut your eyes) and climbing a rickety staircase, is the ghetto. It seems to be reserved exclusively for women and foreigners. Anyone taller than 5’9” will have to watch their heads. Leader-for-life Heydar Aliyev smiles benevolently at the cockroaches that skitter across the dirty wallpaper.

No one comes the Pork Chop Shop for the atmosphere.

PCS’s small plates are completely unremarkable – stale bread, lifeless pickled cabbage and skimpy cheese portions.

But no one comes to the Pork Chop Shop for the salads, either.

I don't eat pork at home and when it comes to food on the road, my policy is to eat what locals eat and avoid things they don't. Pork in a Muslim country falls firmly into that category. But even I, a known swinophobe, could see that these chops are worth taking a chance on.

The chops served here are not your mother's chops (at least not my mother's). They are as long as your forearm, with a thick fist of glossy meat at the end. This meat isn't dull white or gristly or dry as a dishtowel like the chops I remember. It is caramel colored and dappled with the hot, rich kind of fat that pools up in the pan after you fry up your bacon. Cooked over an open fire, the fatty edge of the chop has a thin crust, no harder to break with your teeth than that on a creme brulee.

Thick and Glossy Meat

PCS also serves traditional Azeri fare – kebabs, kebabs and more kebabs. Even vegetarians rave about the potato lula -- mashed potatoes cooked on a skewer. Veggies have to be willing to overlook the occasional pork shrapnel in the potatoes, however.

If you want to ensure PCS has ample chops and cold beer on hand, it’s not a bad idea to call ahead. Price is no obstacle, even for the most impecunious. Endless plates of chops along with more vodka and beer than you should drink in one sitting should set you back no more than five Shirvan ($10).

Where else in Baku can you hit the trifecta (pork, liquor and cigarettes)with such style? This chop shop is worth going out of your way for.

Xayal Kafe is located on Fuzuli Street, directly across from the orange Milli Bank. Look for the yellow sign.

Pork Chop Shop

Nothing about Xayal Kafe’s dowdy exterior hints at the forbidden fruit served inside. But this little hole in the wall – known among expats as The Pork Chop Shop -- is Muslim Baku's swine speakeasy.

The Pork Chop Shop (PCS) sits on a chaotic street near the train station, tucked among cell phone vendors and currency exchanges. It's furnished modestly, with molded plastic seats. Azeri men sit huddled at small tables, sipping tea and looking askance at women who step in through the front door.

The claustrophobic upstairs “loft,” reached by passing through the kitchen (shut your eyes) and climbing a rickety staircase, is the ghetto. It seems to be reserved exclusively for women and foreigners. Anyone taller than 5’9” will have to watch their heads. Leader-for-life Heydar Aliyev smiles benevolently at the cockroaches that skitter across the dirty wallpaper.

No one comes the Pork Chop Shop for the atmosphere.

PCS’s small plates are completely unremarkable – stale bread, lifeless pickled cabbage and skimpy cheese portions.

But no one comes to the Pork Chop Shop for the salads, either.

I don't eat pork at home and when it comes to food on the road, my policy is to eat what locals eat and avoid things they don't. Pork in a Muslim country falls firmly into that category. But even I, a known swinophobe, could see that these chops are worth taking a chance on.

The chops served here are not your mother's chops (at least not my mother's). They are as long as your forearm, with a thick fist of glossy meat at the end. This meat isn't dull white or gristly or dry as a dishtowel like the chops I remember. It is caramel colored and dappled with the hot, rich kind of fat that pools up in the pan after you fry up your bacon. Cooked over an open fire, the fatty edge of the chop has a thin crust, no harder to break with your teeth than that on a creme brulee.

Thick and Glossy Meat

PCS also serves traditional Azeri fare – kebabs, kebabs and more kebabs. Even vegetarians rave about the potato lula -- mashed potatoes cooked on a skewer. Veggies have to be willing to overlook the occasional pork shrapnel in the potatoes, however.

If you want to ensure PCS has ample chops and cold beer on hand, it’s not a bad idea to call ahead. Price is no obstacle, even for the most impecunious. Endless plates of chops along with more vodka and beer than you should drink in one sitting should set you back no more than five Shirvan ($10).

Where else in Baku can you hit the trifecta (pork, liquor and cigarettes)with such style? This chop shop is worth going out of your way for.

Xayal Kafe is located on Fuzuli Street, directly across from the orange Milli Bank. Look for the yellow sign.

Review: Kafe Sheki

Kafe Sheki

When you’re in the mood for cheap Azeri food but are tired of greasy lula kabobs and run-of-the-mill cucumber salad, head out for a place like Kafe Sheki that offers traditional kebabs with a twist and platefuls of regional specialties.

Baku has many such cafes, designed to remind urban migrants of their home regions. Kafe Sheki serves up meals typical of the mountainous region, omitting the six hour drive on bad roads.

An order of mixed kebabs comes with tart chicken breasts soaked in vinegar (toyuq kebab) and a house specialty --cubes of beef marinated in spices called basdirma kebab. The aftertaste is a complex blend of cumin and mint, rather than the usual palate-coating film of fat.

Another tasty and unique kebab is the bildirchin, or marinated quail. Also, a restaurant that serves Sheki specialties can be counted on for excellent Piti. Piti, which is sort of a chickpea stew with globules of assfat floating in it is, admittedly, an acquired taste.

Round out your meal with tea served with homemade cherry or raspberry jams. Tea service also comes with a plate of homemade sugars (ev gendi) to drop in your glass or eat like candy. The famous sticky-sweet Sheki halva is also a desert option.

Kafe Sheki’s atmosphere is much more agreeable than the white tile floors and molded plastic furniture typical of many small cafes. Snack on pickled zoghal (a sour seeded red fruit that seems to have no European or American equivalent), fresh pendir and white pickled cucumbers in rustic wooden cabin-like booths accessorized by sheep and goat skins. Strings of garlic, onions, sweet corn, and incongruously, a coconut, hang from the ceilings and walls.

With its décor that toes the fine line between kitschy and comfy, and its tasty kebabs, pickles and deserts, Kafe Sheki is a fine way to visit the mountains without dropping more than five Shirvan a person.

Kafe Sheki is located at 8 Axundov street, about a block past the railroad overpass.

When you’re in the mood for cheap Azeri food but are tired of greasy lula kabobs and run-of-the-mill cucumber salad, head out for a place like Kafe Sheki that offers traditional kebabs with a twist and platefuls of regional specialties.

Baku has many such cafes, designed to remind urban migrants of their home regions. Kafe Sheki serves up meals typical of the mountainous region, omitting the six hour drive on bad roads.

An order of mixed kebabs comes with tart chicken breasts soaked in vinegar (toyuq kebab) and a house specialty --cubes of beef marinated in spices called basdirma kebab. The aftertaste is a complex blend of cumin and mint, rather than the usual palate-coating film of fat.

Another tasty and unique kebab is the bildirchin, or marinated quail. Also, a restaurant that serves Sheki specialties can be counted on for excellent Piti. Piti, which is sort of a chickpea stew with globules of assfat floating in it is, admittedly, an acquired taste.

Round out your meal with tea served with homemade cherry or raspberry jams. Tea service also comes with a plate of homemade sugars (ev gendi) to drop in your glass or eat like candy. The famous sticky-sweet Sheki halva is also a desert option.

Kafe Sheki’s atmosphere is much more agreeable than the white tile floors and molded plastic furniture typical of many small cafes. Snack on pickled zoghal (a sour seeded red fruit that seems to have no European or American equivalent), fresh pendir and white pickled cucumbers in rustic wooden cabin-like booths accessorized by sheep and goat skins. Strings of garlic, onions, sweet corn, and incongruously, a coconut, hang from the ceilings and walls.

With its décor that toes the fine line between kitschy and comfy, and its tasty kebabs, pickles and deserts, Kafe Sheki is a fine way to visit the mountains without dropping more than five Shirvan a person.

Kafe Sheki is located at 8 Axundov street, about a block past the railroad overpass.

Review: Traktir Na Malakansky

Traktir Na Malakansky

If your idea of “comfort food” is brown bread, mushroom blini and “classic” stroganoff, try out Traktir na Molokansky for a homey Russian meal. In a convenient location, Traktir’s rustic but warm interior suggests dark winter nights in the village, illuminated by music, good friends and clear liquor.

Traktir offers familiar Russian dishes such as borscht, herring shuba salad and an assortment cold and hot platters. Some of the main dishes are outstanding, particularly the sweet and tender duck stuffed with apple or apricot. Rabbit in wine sauce is another winning combination (provided its duck and wabbit season). In a nod to the Caspian kitchen, Traktir offers three different sturgeon options – boiled, Volga or Monastic.

Wrap up your meal with an assortment of sweet or savory blini. Sweet “flour” plates are accompanied by fruit compote or smetana (sweet, heavy cream), which is possibly Russia’s greatest contribution to the world’s array of condiments.

In addition to Georgian wines, Traktir has an impressive list of vodkas to animate dinner table debate. Order a plate of pickles to ease the conversational transition from the plight of the peasant to the vulgarity of the oligarchs.

With its dark wood walls, exposed beams and dim lights, Traktir is moody and slightly melancholic. A talented gray-haired man plays both piano and accordion, alternating maudlin Russian favorites with western elevator tunes. Sometimes staff and patrons burst into song, while the passive nudes hanging on the walls look on without passing judgment.

Traktir’s attentive and polite service makes it more enjoyable than the average Russian dining experience. Rather than impeding the ordering process, the wait staff usually facilitates it by being cooperative and helpful, even with foreigners who are unfamiliar with the dishes or mispronounce words. Traktir provides a menu in English, the contents of which are almost always available.

Traktir Na Molokansky is at 6 Hajibeyov, facing Molokan Garden.

If your idea of “comfort food” is brown bread, mushroom blini and “classic” stroganoff, try out Traktir na Molokansky for a homey Russian meal. In a convenient location, Traktir’s rustic but warm interior suggests dark winter nights in the village, illuminated by music, good friends and clear liquor.

Traktir offers familiar Russian dishes such as borscht, herring shuba salad and an assortment cold and hot platters. Some of the main dishes are outstanding, particularly the sweet and tender duck stuffed with apple or apricot. Rabbit in wine sauce is another winning combination (provided its duck and wabbit season). In a nod to the Caspian kitchen, Traktir offers three different sturgeon options – boiled, Volga or Monastic.

Wrap up your meal with an assortment of sweet or savory blini. Sweet “flour” plates are accompanied by fruit compote or smetana (sweet, heavy cream), which is possibly Russia’s greatest contribution to the world’s array of condiments.

In addition to Georgian wines, Traktir has an impressive list of vodkas to animate dinner table debate. Order a plate of pickles to ease the conversational transition from the plight of the peasant to the vulgarity of the oligarchs.

With its dark wood walls, exposed beams and dim lights, Traktir is moody and slightly melancholic. A talented gray-haired man plays both piano and accordion, alternating maudlin Russian favorites with western elevator tunes. Sometimes staff and patrons burst into song, while the passive nudes hanging on the walls look on without passing judgment.

Traktir’s attentive and polite service makes it more enjoyable than the average Russian dining experience. Rather than impeding the ordering process, the wait staff usually facilitates it by being cooperative and helpful, even with foreigners who are unfamiliar with the dishes or mispronounce words. Traktir provides a menu in English, the contents of which are almost always available.

Traktir Na Molokansky is at 6 Hajibeyov, facing Molokan Garden.

Wednesday, November 02, 2005

This is much richer than the REAL reality

REALITY SHOW IN AZERBAIJAN

BAKU/31.10.05/TURAN: The first reality-show in Azerbaijan, "Gefes", a joint project of the TV company Azad Azerbaycan and Azercell (GencSim) was announced today.

Such shows are popular all over the world, and now one will take place in Azerbaijan. "Gefes" is a flat in which 13 people of different ages, from 18 to 30 live. For more than 4 months, TV viewers will watch the life of these people on the air.

I would love to write the script for such a show.

BAKU/31.10.05/TURAN: The first reality-show in Azerbaijan, "Gefes", a joint project of the TV company Azad Azerbaycan and Azercell (GencSim) was announced today.

Such shows are popular all over the world, and now one will take place in Azerbaijan. "Gefes" is a flat in which 13 people of different ages, from 18 to 30 live. For more than 4 months, TV viewers will watch the life of these people on the air.

I would love to write the script for such a show.

Fall Re-Runs: Thanksgiving in Baku

The alligators are snapping their jaws uncomfortably close to my ass, so I am going to resort to pre-blog re-runs. Sorry for those of you who read this email last Thanksgiving, but I thought it was worth posting. Little of it has changed. However, I may be thankful for different things after next week.

Thanksgiving in Baku: A Drama in Several Acts.

Act I: Assemble guest list

Among all the local roughnecks, roustabouts and snaggle-tooth rig monkeys who haven’t the means or will to go home, we were faced with the difficult task of whom to invite to Thanksgiving dinner. In general, all newcomers to Baku are accepted or rejected by the rest of us based on their ability to amuse. Our dinner party invitations are usually extended using the same criteria. Perhaps out of a sense of generosity brought about by the season or, more likely, boredom with the usual suspects, we pretty much opened the event up to anyone who is breathing. This is how we ended up with a guest list of 16 people.

Act II: Make contingency plans

There’s no evidence our oven works properly, and the margin for error with a turkey is pretty narrow. Not only did I return from Tbilisi, Georgia with 7 bottles of Georgian wine and grapeskin vodka, I also bought a bottle of duty-free gin at the airport. Enough of all that, and no one will notice if we have to slip out and run down to the corner rotisserie chicken stand.

Act III: Begin hoarding, I mean, accumulating traditional ingredients

Since the overwhelming majority of expats here are British oil workers, most of the foreign supermarkets cater to their rather coarse British palates. In other words, if you need a can of beans for your toast or some mash for your bangers, you’re in luck, but if you want Coolwhip or a can of Libby’s pumpkin pie mix, you’d better start shopping early, think creatively and save your money. At $10 a kilo, I’ve had to reconsider whether celery is really vital for a quality stuffing. A friend got me a dented can of cranberries from the embassy store. The peeling label shows its jellied contents, complete with the can marks.

I also go to the local version of Costco, also known as the Teze Bazaar (New Bazaar). It’s the largest bazaar in the city and if it’s not there, it doesn’t exist. There are no cranberries and no sweet potatoes. Lots of turnips, though, and more sheep’s heads than I need this week.

Act IV: Inventory kitchen utensils

Turkey pan? Nope. Potato peeler? No. Meat thermometer? Ha. Spatula? No. Gravy boat? Nada. Turkey baster? Nyet. Casseroles? Nein. Adequate serving and glassware? No way. From where all this equipment is going to come is not yet clear. Williams Sonoma hasn’t yet opened its Baku branch. I have been to five stores and two bazaars and have managed to find only the potato peeler and the spatula.

Act V: Investigate local alternatives to traditional dishes

We don’t have cranberries, but I bet pomegranates would be just as good. No sweet potatoes, either, but our cleaning lady's cabbage and beet salads could be a suitable replacement. An Azeri-style plate of palate-cleansing fresh herbs – miniature scallions, basil, parsley and fennel shoots – is a great idea. And what could be more Thanksgiving-y than beluga caviar from an endangered Caspian sturgeon poached by the government-owned fish processing operation?

Act VI: Get the Turkey

Azerbaijan is lousy with wiry hens and toms that travel in large herds and occasionally block traffic. In fact, one of my local staff who has enjoyed a real American thanksgiving dinner in the States helpfully suggested that, while we were out in the regions for work, we buy a live country turkey -- which everyone knows are measurably better than their city-raised cousins -- and transport it back to Baku the trunk of our white Volga. Once home, she explained, I could keep it on our balcony until Thanksgiving.

I suggested that where to keep the turkey for a week was actually not the biggest logistical problem associated with her otherwise very good idea.

“I don’t know what you’re so concerned about,” my American co-worker contributed. “You know you could walk out your back door and anyone on the street would kill and clean it for you for a Shirvan. ($2)”

As tempting as those ideas were, I decided to take a more traditional approach: enlist the services of my very resourceful driver, Rashid.

Rashid is the kind of guy that every expat needs to have around. His skills far exceed his ability to watch his dashboard DVD player and drive at the same time. In his 30’s, with a broad smile of gold teeth, he comes from a long line of native Bakuvians and brags about his knowledge of the city. He is THE source for the best caviar (“Sevruga, never!”) and can get kegs of Azerbaijan’s unpasteurized, déclassé NZS beer, which, even though it is the only drinkable local brew, is only sold draft in male-only, basement pivesis. Whatever you need, Rashid can get it.

Rashid and I headed out to the Teze Bazaar. “Are you going to clean it yourself?” Rashid asked. I had to explain that turkeys where I come from are tightly wrapped in dense plastic, have their guts neatly bagged and stuffed in the neck hole and have red pop-out timers to indicate their doneness. Whoever sells us the bird, I emphasized, would be responsible not only for snuffing out its life force, but for removing its inedible bits as well.

We took a look at the pen of live turkeys. These lanky birds spent their lives not in cages, but running free and wild, pecking at rocks, grass and sheep poops. But where were their breasts? Meaty legs? Fortunately, we found a woman with a bright green floral headscarf peddling slightly larger birds that were already dead and freshly plucked. “Killed just two hours ago! Smell!” she said, pushing the turkey’s neck cavity into my face. I had prepared myself to play turkey executioner, and was somewhat relieved to find one with whom I had not yet established a personal relationship.

I bought two. At five and eight pounds, they’re not big enough -- not even close -- for 16 people. Someone is going to have to go to the rotisserie chicken stand. Maybe no one will notice.

Final Act: Be Thankful

I am thankful we are not in the mountains of Ethiopia, eating bread and yoghurt for dinner, like last year. I am thankful that the US is probably not going to invade Azerbaijan right away. I am thankful we do not live in Minsk or Tashkent. I am thankful we have 16 people coming over for dinner, instead of no one. I am thankful that I do not pay US taxes. I am thankful every time I ride in a car here without getting in an accident. I am thankful that I can smell the bad smell coming from the bathroom drain only in the morning. I am thankful that shameless consumerism enters my life only when I need it. I am thankful that I was mistaken for a common prostitute only once this week. I am thankful that karaoke is not that popular here.

You should be thankful too.

Thanksgiving in Baku: A Drama in Several Acts.

Act I: Assemble guest list

Among all the local roughnecks, roustabouts and snaggle-tooth rig monkeys who haven’t the means or will to go home, we were faced with the difficult task of whom to invite to Thanksgiving dinner. In general, all newcomers to Baku are accepted or rejected by the rest of us based on their ability to amuse. Our dinner party invitations are usually extended using the same criteria. Perhaps out of a sense of generosity brought about by the season or, more likely, boredom with the usual suspects, we pretty much opened the event up to anyone who is breathing. This is how we ended up with a guest list of 16 people.

Act II: Make contingency plans

There’s no evidence our oven works properly, and the margin for error with a turkey is pretty narrow. Not only did I return from Tbilisi, Georgia with 7 bottles of Georgian wine and grapeskin vodka, I also bought a bottle of duty-free gin at the airport. Enough of all that, and no one will notice if we have to slip out and run down to the corner rotisserie chicken stand.

Act III: Begin hoarding, I mean, accumulating traditional ingredients

Since the overwhelming majority of expats here are British oil workers, most of the foreign supermarkets cater to their rather coarse British palates. In other words, if you need a can of beans for your toast or some mash for your bangers, you’re in luck, but if you want Coolwhip or a can of Libby’s pumpkin pie mix, you’d better start shopping early, think creatively and save your money. At $10 a kilo, I’ve had to reconsider whether celery is really vital for a quality stuffing. A friend got me a dented can of cranberries from the embassy store. The peeling label shows its jellied contents, complete with the can marks.

I also go to the local version of Costco, also known as the Teze Bazaar (New Bazaar). It’s the largest bazaar in the city and if it’s not there, it doesn’t exist. There are no cranberries and no sweet potatoes. Lots of turnips, though, and more sheep’s heads than I need this week.

Act IV: Inventory kitchen utensils

Turkey pan? Nope. Potato peeler? No. Meat thermometer? Ha. Spatula? No. Gravy boat? Nada. Turkey baster? Nyet. Casseroles? Nein. Adequate serving and glassware? No way. From where all this equipment is going to come is not yet clear. Williams Sonoma hasn’t yet opened its Baku branch. I have been to five stores and two bazaars and have managed to find only the potato peeler and the spatula.

Act V: Investigate local alternatives to traditional dishes

We don’t have cranberries, but I bet pomegranates would be just as good. No sweet potatoes, either, but our cleaning lady's cabbage and beet salads could be a suitable replacement. An Azeri-style plate of palate-cleansing fresh herbs – miniature scallions, basil, parsley and fennel shoots – is a great idea. And what could be more Thanksgiving-y than beluga caviar from an endangered Caspian sturgeon poached by the government-owned fish processing operation?

Act VI: Get the Turkey

Azerbaijan is lousy with wiry hens and toms that travel in large herds and occasionally block traffic. In fact, one of my local staff who has enjoyed a real American thanksgiving dinner in the States helpfully suggested that, while we were out in the regions for work, we buy a live country turkey -- which everyone knows are measurably better than their city-raised cousins -- and transport it back to Baku the trunk of our white Volga. Once home, she explained, I could keep it on our balcony until Thanksgiving.

I suggested that where to keep the turkey for a week was actually not the biggest logistical problem associated with her otherwise very good idea.

“I don’t know what you’re so concerned about,” my American co-worker contributed. “You know you could walk out your back door and anyone on the street would kill and clean it for you for a Shirvan. ($2)”

As tempting as those ideas were, I decided to take a more traditional approach: enlist the services of my very resourceful driver, Rashid.

Rashid is the kind of guy that every expat needs to have around. His skills far exceed his ability to watch his dashboard DVD player and drive at the same time. In his 30’s, with a broad smile of gold teeth, he comes from a long line of native Bakuvians and brags about his knowledge of the city. He is THE source for the best caviar (“Sevruga, never!”) and can get kegs of Azerbaijan’s unpasteurized, déclassé NZS beer, which, even though it is the only drinkable local brew, is only sold draft in male-only, basement pivesis. Whatever you need, Rashid can get it.

Rashid and I headed out to the Teze Bazaar. “Are you going to clean it yourself?” Rashid asked. I had to explain that turkeys where I come from are tightly wrapped in dense plastic, have their guts neatly bagged and stuffed in the neck hole and have red pop-out timers to indicate their doneness. Whoever sells us the bird, I emphasized, would be responsible not only for snuffing out its life force, but for removing its inedible bits as well.

We took a look at the pen of live turkeys. These lanky birds spent their lives not in cages, but running free and wild, pecking at rocks, grass and sheep poops. But where were their breasts? Meaty legs? Fortunately, we found a woman with a bright green floral headscarf peddling slightly larger birds that were already dead and freshly plucked. “Killed just two hours ago! Smell!” she said, pushing the turkey’s neck cavity into my face. I had prepared myself to play turkey executioner, and was somewhat relieved to find one with whom I had not yet established a personal relationship.

I bought two. At five and eight pounds, they’re not big enough -- not even close -- for 16 people. Someone is going to have to go to the rotisserie chicken stand. Maybe no one will notice.

Final Act: Be Thankful

I am thankful we are not in the mountains of Ethiopia, eating bread and yoghurt for dinner, like last year. I am thankful that the US is probably not going to invade Azerbaijan right away. I am thankful we do not live in Minsk or Tashkent. I am thankful we have 16 people coming over for dinner, instead of no one. I am thankful that I do not pay US taxes. I am thankful every time I ride in a car here without getting in an accident. I am thankful that I can smell the bad smell coming from the bathroom drain only in the morning. I am thankful that shameless consumerism enters my life only when I need it. I am thankful that I was mistaken for a common prostitute only once this week. I am thankful that karaoke is not that popular here.

You should be thankful too.